Surviving the unthinkable: Keith Edmonds’ fight for life

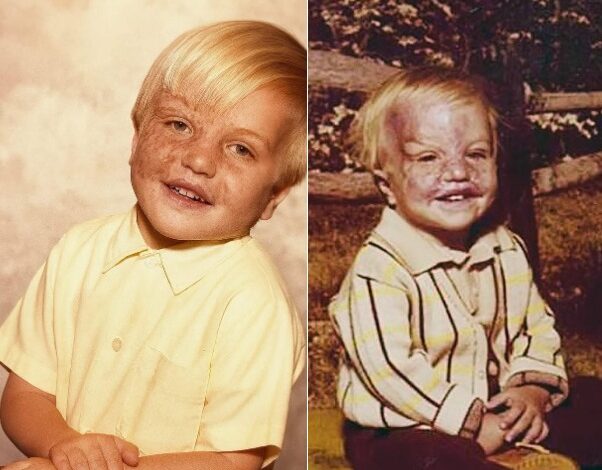

The narrative arc of Keith Edmonds’ life was nearly severed before he could even form his first memories. In a chilling case of domestic brutality that remains a haunting footnote in Flint, Michigan’s history, Edmonds—then a mere fourteen months old—found himself the target of an unimaginable rage. On November 18, 1978, a toddler’s cries triggered a violent outburst from his mother’s boyfriend. The man held the infant’s face directly against the searing coils of an electric heater, inflicting third-degree burns across half of his face and forever altering the child’s physical and psychological trajectory.

At the hospital, the prognosis was grim. “I spent a month in the hospital, with no one knowing if I was going to live or die,” Keith recalls. Doctors braced the family for the worst, yet Edmonds defied the clinical expectations of the era. He survived, transitioning into a childhood defined by a grueling odyssey of skin grafts and reconstructive procedures at the Shriners Burn Institute in Cincinnati—a medical marathon that would continue until he was eighteen years old.

The Failure of the Gavel

While the medical community worked to rebuild his face, the judicial system offered little in the way of restitution. Edmonds’ abuser was sentenced to just ten years in prison—a term that, in retrospect, feels like a shocking light-handedness given the severity of the crime. For the young victim, the brevity of the sentence served as a secondary trauma.

“When I was a younger child and into my teenage years, I absolutely did not believe 10 years was enough,” Edmonds told Newsner. The sense of betrayal by the courts fueled a dark, retaliatory fire. “I was looking for him… I was willing to meet him face to face and get revenge.” Fortunately, he never found the man. However, the internal wreckage persisted.

Edmonds became a ward of the state, navigating the often-volatile foster care system before eventually being reunited with his mother after she was cleared of wrongdoing. But the scars—visible to every stranger on the street—led to relentless bullying and a profound sense of isolation. By age thirteen, Edmonds began self-medicating with alcohol, embarking on a twenty-year spiral into addiction, depression, and recurring brushes with the law.

The 35th Birthday Epiphany

The trajectory of self-destruction reached a sudden, dramatic halt on July 9, 2012. On his 35th birthday, in the midst of another bender, Edmonds experienced what he describes as a moment of absolute clarity. “I wanted to become a better person,” he says. That single decision became the pivot point for a radical life redesign.

Edmonds didn’t just get sober; he excelled. He entered the high-stakes world of corporate sales, finding unprecedented success with tech giant Dell and later the Coca-Cola Company. At Coca-Cola, management recognized a unique grit in Edmonds, assigning him the most challenging sales routes in inner-city Detroit. Where others saw risk, Edmonds saw connection. His ability to build rapport in overlooked communities consistently earned him top-tier awards, but his ambition was soon pulled toward a higher calling.

Purpose Born of Pain: The Keith Edmonds Foundation

In 2016, Edmonds codified his survival into a mission, establishing the Keith Edmonds Foundation. The non-profit is designed to address the specific gaps in support for abused and neglected children. Two flagship programs have emerged as life-lines:

- Backpacks of Love: Providing foster children with essential dignity by supplying quality items for their first days in a new placement.

- Camp Confidence: A summer initiative that pairs abuse survivors with mentors to foster empowerment and self-worth.

Edmonds recalls a poignant moment at the camp when a young girl asked an adult survivor if he could be her role model. “There was such a great connection there,” Edmonds says. “I was so overcome, I had to leave the room.”

For Edmonds, the work is about sustained presence, not fleeting charity. “We can’t just come into their lives for the camp and then just leave,” he insists. “We walk alongside them.”

The Credibility of the Scar

In the world of motivational speaking, authenticity is the only currency that matters. Rick Miller, principal of MAP Academy for at-risk students in Lebanon, Tennessee, notes that Edmonds possesses a rare, immediate trust with students. “They relate to him because he wears the scars of his abuse every day of his life and he doesn’t shoot them full of hot air,” Miller explains.

This credibility has saved lives. Miller recalls a high school girl who was on the brink of being “lost” to her trauma until she met Keith and his wife, Kelly. “She became like a new kid. I watched her smile again and saw life coming back to her,” he says.

Edmonds views his physical appearance as a bridge rather than a barrier. “There are people who wear their scars all on the inside and you pass them every day,” he observes. “I just happen to wear my scars on the inside and the outside.”

The Final Frontier: Forgiveness

Perhaps the most remarkable chapter of Edmonds’ story is his stance on his attacker. Today, Edmonds knows exactly where the man lives—a town not far from his own doorstep. Yet, the rage that consumed his twenties has been replaced by a sophisticated, hard-won peace.

“At 35, when I got sober and worked on myself… I again found this thing called forgiveness,” he shares. For Edmonds, forgiveness isn’t about exoneration; it’s about emotional hygiene. “It does not excuse the person’s actions… but it truly does give you a better perspective on life.” He has chosen not to seek a confrontation, noting that if they did meet, it likely wouldn’t be met with anger.

His capacity for forgiveness extends to his mother as well. Despite the turbulent years documented in his book, Scars: Leaving Pain in the Past, the two remain in contact.

Keith Edmonds’ journey—from a fourteen-month-old fighting for air in 1978 to a beacon of corporate and philanthropic success in 2026—serves as a definitive proof of concept for human resilience. He has successfully transitioned from victim to survivor, and finally, to a mentor. As he puts it: “I quit drinking for every child that has been affected by child abuse… it is my job to help empower and assist others in their journeys. And try my best to shorten their transition.”